✰ Entrevista NIRVANA_16 DE ABRIL 1992 - RollingStone magazine (sesión fotos Mark Seliger) (ver fotos)

NIRVANA Entrevistados por Michael Azerrad

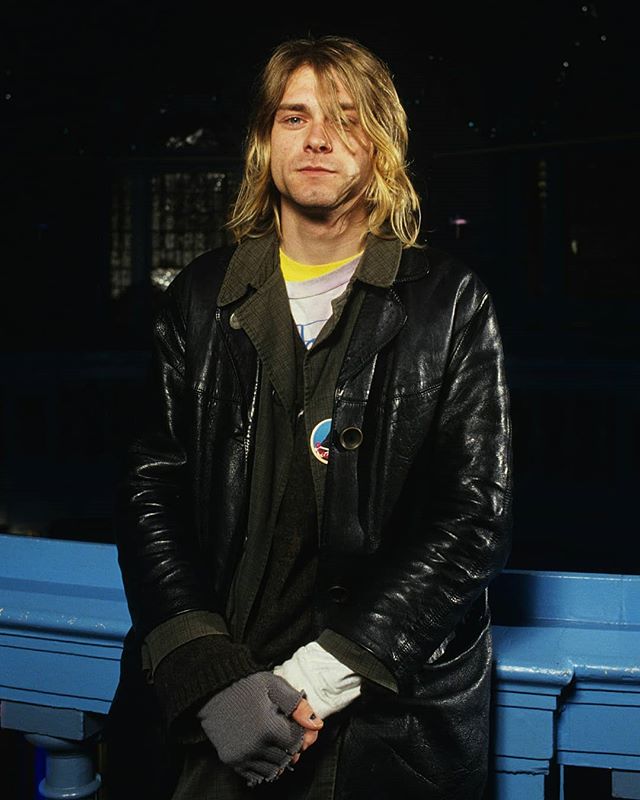

Inside the Heart and Mind of Kurt Cobain

For now, Nirvana leader Kurt Cobain and his new wife, Courtney Love, live in an apartment in Los Angeles’s modest Fairfax district. The living room holds little besides a Fender Twin Reverb amplifier, a stringless guitar, a makeshift Buddhist shrine and, on the mantel, the couple’s collection of naked plastic dolls.

Scores of CDs and tapes are strewn around the stereo – obscurities such as Calamity Jane, Cosmic Psychos and Billy Childish, as well as Cheap Trick and the Beatles. “Norwegian Wood” drifts down the hall to the dimly lit bedroom, where Cobain lies flat on his back in striped pajamas, a red-painted big toenail peeking out the other end of the blanket and a couple of teddy bears lying beside him for company. The surprisingly fragrant Los Angeles night seeps through the window screen.

He’s been suffering from a long-standing and painful stomach condition – perhaps probably an ulcer – aggravated by stress and, apparently, his screaming singing style. Having eaten virtually nothing for over more than two weeks, Cobain is strikingly gaunt and frail, far from the stubbly doughboy who smirked out from a photo inside Nevermind. It’s hard to believe this is the same guy who smashes guitars and wails with such violence – until you notice his blazing blue eyes and the faded pink and purple streaks in his hair.

Cobain had abruptly canceled an earlier interview, partly because of the anti-Nirvana letters that recently dominated Rolling Stone‘s Correspondence page and partly because the magazine borrowed the title of the band’s hit single “Smells Like Teen Spirit” for a headline on the recent Beverly Hills, 90210 cover.

Then he came around. “There are a lot of things about Rolling Stone that I’ve never agreed with,” says Cobain in a gentle growl one or two steps up from a whisper. “But it’s just so old school to fight amongst your peers or people that are dealing with rock & roll, whether or not they’re dealing with it in the same context that you would like to. There are a lot of political articles in there that I’ve been thankful for, so it’s really stupid to attack something that you’re not 100 percent opposed to. If there’s a glimmer of hope in anything, you should support it.

“I don’t blame the average seventeen-year-old punk-rock kid for calling me a sellout,” Cobain adds. “I understand that. And maybe when they grow up a little bit, they’ll realize there’s more things to life than living out your rock & roll identity so righteously.”

All I need is a break and my stress will be over with,” says the twenty-five-year-old Cobain. “I’m going to get healthy and start over.”

He’s certainly earned a break after playing nearly 100 dates on four continents in five months, never staying in one place long enough for to have a doctor to tend to his stomach problem. And he and his band mates, bassist Chris Novoselic (pronounced nova-SELL-itch) and drummer Dave Grohl, have had to cope with the peculiar position of being the world’s first triple-platinum punk-rock band.

Soon after the September release of Nevermind, MTV pumped “Teen Spirit” night and day as the album vaulted up the charts until it hit Number One. Although the band’s label, DGC, doubted the album would sell over more than 250,000 copies, it sold 3 million in just four months and continues to sell nearly 100,000 copies a week.

For Nirvana, putting out their first major-label record was like getting into a new car. But the runaway success was like suddenly discovering that the car was a Ferrari and the accelerator pedal was Krazy Glued to the floorboard. Friends worried about how the band was dealing with it all.

“Dave’s just psyched,” says Nils Bernstein, a good friend of the band members’ who coordinates their fan mail. “He’s twenty-two, and he’s a womanizer, and he’s just: ‘Score!”’ Novoselic, according to Bernstein, had a drinking problem but went on the wagon this year so he could stay on top of his exploding career.

But rumors are flying about Cobain. A recent item in the music-industry magazine Hits said Cobain was “slam dancing with Mr. Brownstone,” Guns n’ Roses slang for doing heroin. A January profile in BAM magazine claimed Cobain was “nodding off in mid-sentence,” adding that “the pinned pupils, sunken cheeks and scabbed, sallow skin suggest something more serious than mere fatigue.”

Cobain denies he is using heroin. “I don’t even drink anymore because it destroys my stomach,” he protests. “My body wouldn’t allow me to take drugs if I wanted to, because I’m so weak all the time.

“All drugs are a waste of time,” he continues. “They destroy your memory and your self-respect and everything that goes along with your self-esteem. They make you feel good for a little while, and then they destroy you. They’re no good at all. But I’m not going to go around preaching against it. It’s your choice, but in my experience, I’ve found they’re a waste of time.”

Cobain brushes off speculation that he’s finding fame difficult and dismisses rumors that he’ll soon break up the band because it has become too big. “It really isn’t affecting me as much as it seems like it is in interviews and the way that a lot of journalists have portrayed my attitude,” he says. “I’m pretty relaxed with it.”

But people who know him say otherwise. Choosing his words carefully, Jack Endino, producer of the band’s debut album, Bleach, says, “When I saw them in Amsterdam a few months back, it seemed like they were a little grouchy and . . . under pressure, let’s put it that way.” “Kurt is ready to strangle the next person who takes his picture,” adds Bernstein.

Fame rubs against Cobain’s punk ethos, which is why he refused a limo ride to Nirvana’s Saturday Night Live appearance. “People are treating him like a god, and that pisses him off,” says Bernstein. “They’re giving Kurt this elevated sense of importance that he feels he doesn’t have or deserve. So he’s like ‘Fuck you!’

“Chris and Dave have had to pick up a lot of Kurt’s slack,” Bernstein continues. “Chris and Dave were close before, but now they’re inseparable.”

“Just to survive lately I’ve become a lot more withdrawn from the band,” Cobain confesses. “I don’t go party after the show; I go straight to my hotel room and go to sleep and concentrate on eating in the morning. I’d rather deal with things like that. Our friendship isn’t being jeopardized by it, but this tour has definitely taken some years off of our lives. I plan to make changes.”

Stress has gotten to Cobain before. He had an onstage breakdown at a 1989 show in Rome, near the end of a particularly grueling European tour. Says Bruce Pavitt, co-owner of Sub Pop Records, Nirvana’s first label: “After four or five songs, he quit playing and climbed up the speaker column of speakers and was just going to jump off. The bouncers were freaking out, and everybody was just begging him to come down. And he was saying, ‘No, no, I’m just going to dive.’ He had really reached his limit. People literally saw a guy wig out in front of them who could break his neck if he didn’t get it together.” Cobain was eventually talked down.

If he can stand the heat, Cobain, extremely bright and unafraid to take provocative stands, may emerge as a John Lennon-like figure. The comparison with Cobain’s idol isn’t frivolous. Like Lennon, he’s using his music to scream out an unhappy childhood. And like Lennon, he’s deeply in love with an equally provocative and visionary artist – Courtney Love, leader of the fiery neo-feminist band Hole.

Cobain and Love were married on February 24th in a secluded location in Waikiki, Hawaii, after Nirvana’s tour of Japan and Australia, with only a female nondenominational minister and a roadie as a witness.

“It’s like Evian water and battery acid,” Cobain says of the couple’s chemistry. And when you mix the two? “You get love,” says Cobain, smiling for the first time. Exhausted and bedridden, Cobain is still so smitten that he can proclaim: “I’m just happier than I’ve ever been. I finally found someone that I am totally compatible with. It doesn’t matter whether she’s a male, female or hermaphrodite or a donkey. We’re compatible.” Whenever Love walks into the room, even if it’s to scold him about something, he gets the profoundly dopey grin of the truly love struck.

Ihave thought about it, and I can’t come to any conclusions at all,” says Cobain of Nevermind‘s phenomenal success. “I don’t want to sound egotistical, but I know it’s better than a majority of the commercial shit that’s been crammed down people’s throats for a long time.”

Nevermind embodies a cultural moment; “Smells Like Teen Spirit” is an anthem for (or is it rather against) “Why Ask Why?” generation. Just don’t call Cobain a spokesman for a generation. “I’m a spokesman for myself,” he says. “It just so happens that there’s a bunch of people that are concerned with what I have to say. I find that frightening at times because I’m just as confused as most people. I don’t have the answers for anything. I don’t want to be a fucking spokesperson.”

“That ambiguity or confusion, that’s the whole thing,” says Nevermind producer Butch Vig. “What the kids are attracted to in the music is that he’s not necessarily a spokesman for a generation, but all that’s in the music – the passion and [the fact that] he doesn’t necessarily know what he wants but he’s pissed. It’s all these things working at different levels at once. It’s not real cut and dried. I don’t exactly know what ‘Teen Spirit’ means, but you know it means something and it’s intense as hell.”

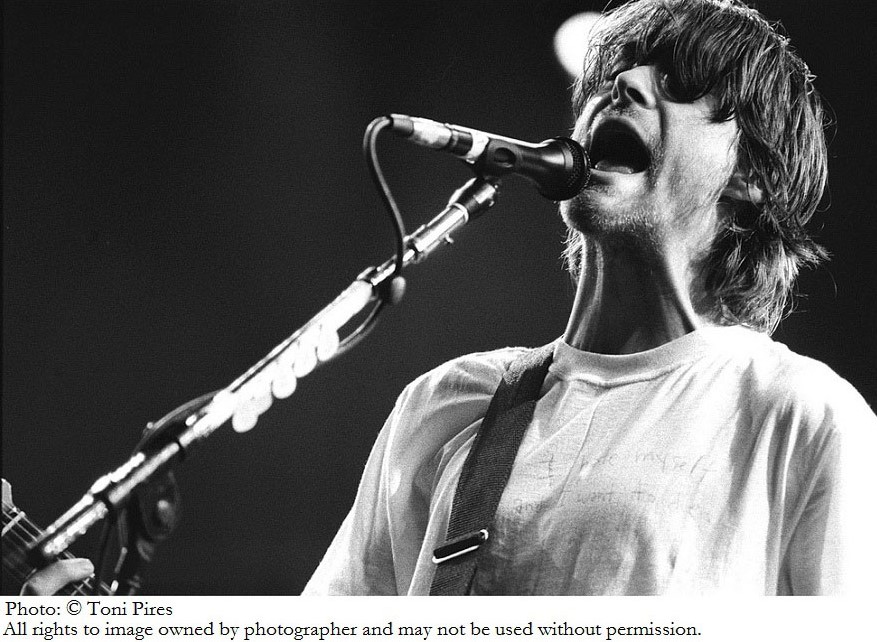

Cobain agrees the message isn’t necessarily in the words. “Most of the music is really personal as far as the emotion and the experiences that I’ve had in my life,” he says, dragging on a cigarette, “but most of the themes in the songs aren’t that personal. They’re more just stories from television or books or movies or friends, more so than mine. But definitely the emotion and feeling is from me.

“Most of the concentration of my singing is from my upper abdomen, that’s where I scream, that’s where I feel, that’s where everything comes out of me – right here,” he continues, touching a point just below his breastbone. It just happens to be exactly where his stomach pain is centered.

When Nevermind hit number one, Cobain was “kind of excited,” he says. “I wouldn’t admit that at the time. I just hope that it doesn’t end with us. I hope there are other bands that can keep it going.”

Although Cobain is thrilled when underground bands infiltrate the mainstream charts, he’s outraged by others who are riding the coattails of the alternative boom. His favorite target is Pearl Jam, also from Seattle, which he accused of “corporate, alternative and cock-rock fusion” in a recent Musician magazine interview. “Every article I see written about them, they mention us, and they’re baiting that fact,” says Cobain, sitting up cross-legged on the bed. “I would love to be erased from my association with that band and other corporate bands like the Nymphs and a few other felons. I do feel a duty to warn the kids of false music that’s claiming to be underground or alternative. They’re jumping on the alternative bandwagon.

“I don’t know what I did to him; if he has a personal vendetta against us, he should come to us,” says Pearl Jam’s Jeff Ament, who says Cobain barely even said hello when they did a recent minitour together. “To have that sort of pent-up frustration, the guy obviously must have some really deep insecurities about himself. Does he think we’re riding his bandwagon? We could turn around and say that Nirvana put out records on money we made for Sub Pop when we were in Green River – if we were that stupid about it.”

Cobain is happier to reel off a list of some of the bands he does like: the Breeders, the Pixies, R.E.M., Jesus Lizard, Urge Overkill, Beat Happening, Mudhoney, Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr and Flipper. Then there’s his beloved Captain America, a ramshackle pop group from Scotland. “Eugene and Frances Kelly are the Lennon and McCartney of the underworld – or the Captain and Tennille,” says Cobain.

For the members of Nirvana, plugging fellow underground musicians is one of the few consolations for the pressures of fame. When the band played Seattle’s Paramount Theater for its big homecoming show last Halloween, its opener was Bikini Kill, a confrontational female-led band from nearby Olympia that came out in lingerie with SLUT written across their stomachs. Novoselic is toying with the idea of a “punk-rock MTV” featuring underground bands.

Helping out fellow alternative types strengthens the community that made Nirvana’s own success possible. “It’s a question of inclusion,” explains Sub Pop co-owner Jonathan Poneman, “it’s a question of being able to be included. Egalitarian revolution – that’s what makes them a punk-rock band.”

It’s fitting that Nirvana bumped Michael Jackson off the Number One spot on the pop charts. Besides a fondness for small children and animals, Cobain and Jackson have little in common – Jackson claims it doesn’t matter if you’re black or white, but when Cobain hears such saccharine platitudes, he screams. Jackson’s music is Eighties-style ear candy, while Nirvana makes grass-roots music for the Nineties. There’s no glamour in Nirvana, no glamour at all, in fact.

Novoselic and Cobain come from rural Aberdeen, Washington, a hundred miles southwest of Seattle, where Novoselic’s mom runs Maria’s Hair Design. A depressed logging town, Aberdeen has seen better days – namely, during the whaling era in the mid-nineteenth century, when the town served as one big brothel for visiting sailors, a fact that Novoselic has said makes residents “a little ashamed of our roots.” Pervasive unemployment and a perpetually rainy, gray climate have led to rampant alcoholism and a suicide rate more than twice the already high state average. The local pawnshop is full of guns, chain saws and guitars.

One of the more popular bars in town is actually called the Pourhouse, which is where two young men about Cobain’s age, Joe and James, sit down for a pitcher of beer – each. Joe is out of work because his leg is broken. “I tried to fly off a house,” he explains.

“Yeah, I know the Cobain kid,” says James. “Faggot.”

“He’s a faggot?” asks Joe, taken aback. Recovering quickly, he declares: “We deal with faggots here. We run ’em out of town.”

This is where Cobain and Novoselic grew up. That’s why they kissed each other full on the lips as the Saturday Night Live credits rolled. They knew it would piss off the folks back home – and everybody like them.

“I definitely have a problem with the average macho man – the strong-oxen working-class type,” Cobain says wearily, “because they have always been a threat to me. I’ve had to deal with them most of my life – being taunted and beaten up by them in school, just having to be around them and be expected to be that kind of person when you grow up.

“I definitely feel closer to the feminine side of the human being than I do the male – or the American idea of what a male is supposed to be,” Cobain continues. “Just watch a beer commercial and you’ll see what I mean.”

Of course, Cobain was miserable in high school. Surrounded by hard-drinking metalheads whose only prospects were unemployment or risking life and limb hacking down beautiful centuries-old trees, Cobain was a sensitive sort, small for his age and uninterested in sports. “He was terrified of jocks and moron dudes,” recalls Cobain’s old friend Mudhoney bassist Matt Lukin.

“As I got older,” says Cobain, a fan of Beckett’s, Burroughs’s and Bukowski’s, “I felt more and more alienated – I couldn’t find friends whom I felt compatible with at all. Everyone was eventually going to become a logger, and I knew I wanted to do something different. I wanted to be some kind of artist.”

“If he would have been anywhere else,” says his mother, Wendy O’Connor, “he would have been fine – there would have been enough of his kind not to stick out so much. But this town is just exactly like Peyton Place. Everybody is watching everyone and judging, and they have their little slots they like everyone to stay in – and he didn’t.”

A friend of Cobain’s half-joked that Nevermind sold to every abused child in the country, and maybe that’s not far from the truth – the divorce rate soared to nearly fifty percent in the mid-Seventies, and all those children of broken homes are becoming adults. Including Kurt Cobain.

Cobain started life as a sunny child. “He got up every day with such joy that there was another day to be had,” recalls his mother. “When we’d go downtown to the stores, he would sing to people.” Cobain’s intelligence was apparent early on. “It kind of scared me because he had perceptions like I’ve never seen a small child have,” his mother continues. “He had life figured out really young. He knew life wasn’t always fair. Kurt was focused on the world – he would be drawing in a coloring book, and the news would be on and he was very attuned to that, and he was just three and a half. He knew all about the war.

“He had make-believe friends, too,” O’Connor says. “There was one called Boda – he blamed everything on him. He had to have a place at the table – it just became ridiculous. One day his uncle Clark asked if he could take Boda with him to Vietnam because he was lonely there. And Kurt took me aside and whispered in my ear: ‘Boda isn’t real. Does Clark know that?’ ”

But Cobain’s parents – a secretary and an auto mechanic – divorced when he was eight, and “it just destroyed his life,” says his mother. “He changed completely. I think he was ashamed. And he became very inward – he just held everything. He became real shy. It just devastated him. I think he’s still suffering.” A bit of a “juvenile,” as he puts it, Cobain was shuffled from his mother to his father, uncles and grandparents and back again.

Cobain listened to nothing but the Beatles until he was nine, when his dad began subscribing to a record club and albums by Led Zeppelin, Kiss and Black Sabbath began arriving in the mail. Then Kurt began following the Sex Pistols‘ American tour in magazines. He didn’t know what punk sounded like, because no store in town stocked the records, but he had an idea. “I was looking for something a lot heavier, yet melodic at the same time,” Cobain says, “something different from heavy metal, a different attitude.”

Cobain idolized the Aberdeen band the Melvins and drove their tour van, hauled their equipment and watched over 200 of their rehearsals, by his estimate. Melvins leader Buzz Osborne became his friend and mentor and took sixteen-year-old Cobain to his first rock show – Black Flag. According to erstwhile Melvins bassist Matt Lukin, “He was totally blown away.” It was about this time that Cobain moved from drums to guitar.

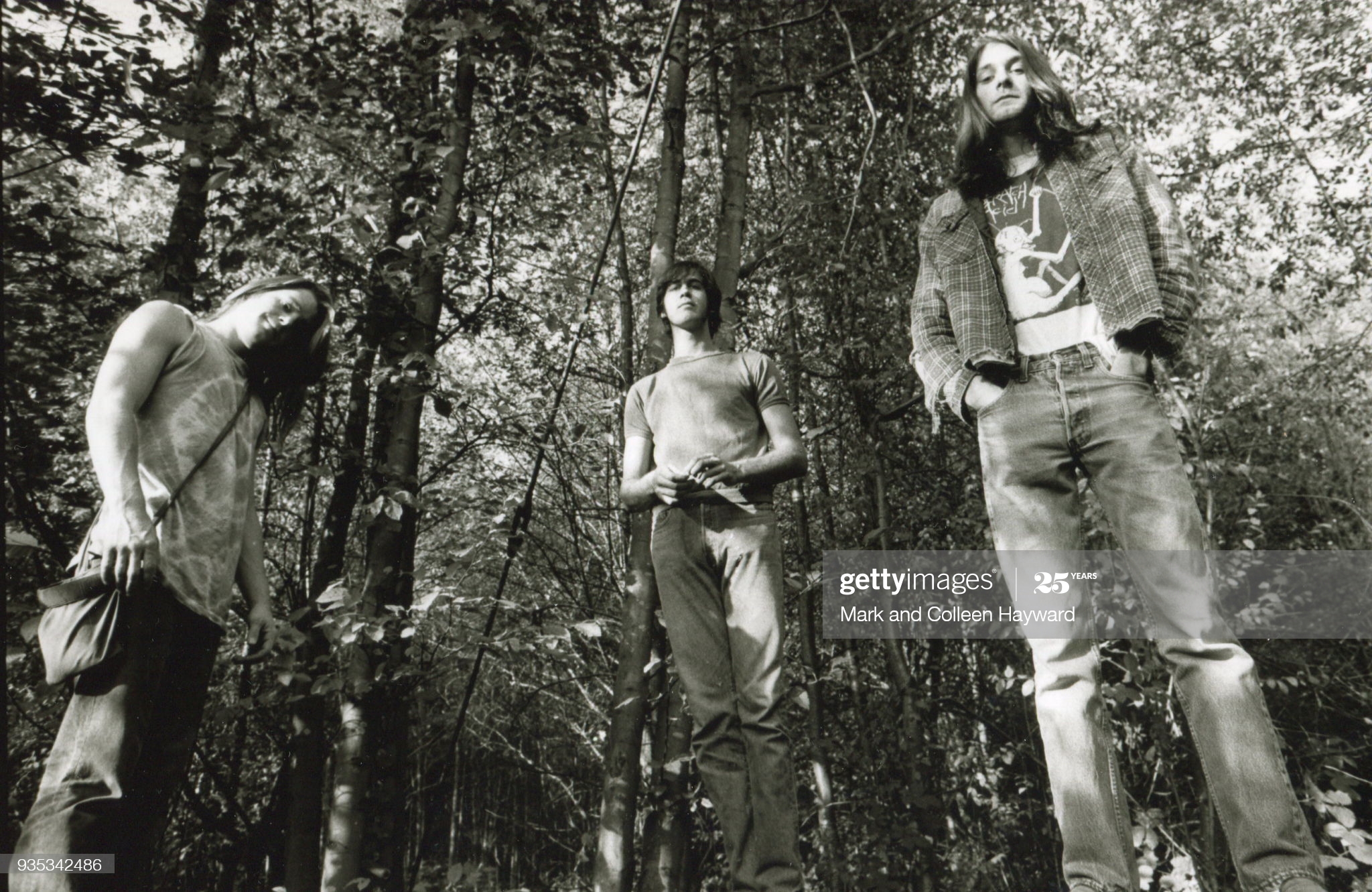

“I don’t think he had a hell of a lot of friends,” Lukin recalls. “He was always trying to start bands, but it was hard to find people who wouldn’t flake out on him.” Osborne introduced him to Novoselic, a shy youth so tall (he’s six foot seven) that he bumped his head on the beams in Cobain’s house. Cobain formed a band with this kindred spirit two years his senior. They went through names like Ed, Ted, and Fred; Skid Row; and Fecal Matter before settling on Nirvana. Nerves and crummy equipment hampered their live attack, but Nirvana slowly developed a powerful sound, becoming very popular in neighboring Olympia, where they would play wild parties at Evergreen State College.

Meanwhile, Cobain’s mother kicked him out of the house after he quit high school and played in bands instead of getting a job. Homeless, Cobain slept on friends’ couches. At one point, he lived under a bridge in Aberdeen, an arrangement chronicled in Nevermind‘s “Something in the Way.”

A vandal with a cause, Cobain loved to spray-paint the word queer on four-by-four trucks, the redneck vehicle of choice. Other favorite graffiti included GOD IS GAY and ABORT CHRIST. In 1985 Novoselic, Osborne and eighteen-year-old Cobain wrote HOMOSEXUAL SEX RULES on the side of an Aberdeen bank (Osborne swears it said, QUIET RIOT). While Osborne and Novoselic hid in a garbage dumpster, Cobain was caught and arrested. A police report lists the contents of his pockets: a guitar pick, a key, a beer, a mood ring and a cassette by the militant punk band Millions of Dead Cops. He received a $180 fine and a thirty-day suspended sentence.

“He is really a very angry person,” says Sub Pop’s Bruce Pavitt, “so he makes dramatic gestures that piss people off.” But Cobain is also sensitive, and sensitive people are often the angriest. “Exactly,” says Pavitt. “That’s the key.”

Cobain took jobs as a janitor at a hotel and at a dentist’s office (where he dipped into the nitrous) and moved in with Matt Lukin, who was then with the Melvins. Just to freak the neighbors, Cobain made a satanic-looking doll and hung it from a noose in his window. He kept some pet turtles in a bathtub that he put in the front room. Then he realized there was no way to drain the water, so Lukin, a carpenter, simply cut a hole in the floor. The foundation eventually became waterlogged, leaving the rickety shack teetering.

In a demo session with producer Jack Endino, one of the patron saints of the Seattle grunge scene, Cobain and Melvins drummer Dale Crover finished ten songs in one afternoon. Impressed, Endino played the tape for Sub Pop’s Jonathan Poneman. (Two cuts wound up on Bleach, and later this year Sub Pop will release a collection of Nirvana rarities.)

At a Seattle coffee shop, Poneman met Cobain, who was awed by Sub Pop because it boasted one of his favorite bands, Soundgarden. Novoselic showed up a bit later. “Chris was drunk and belligerent,” recalls Poneman, “and just didn’t give a flying fuck about it – ‘Okay, you want to put out our records, that’s cool.’ And then he’d insult me.” Poneman signed Nirvana anyway.

A year and two drummers later, in October 1988, Sub Pop released the single “Love Buzz”/”Big Cheese”; Bleach was released in June 1989, recorded for the princely sum of $606.17. (Jason Everman didn’t actually play on the album, although he was credited as a guitarist because he bankrolled the recording. “We still owe him the $600,” says Cobain. “Maybe I should send him off a check.”)

Bleach sold slowly at first, but after a few months critical raves and effusive praise from indie kingpins Sonic Youth eventually helped Bleach to sell 35,000 copies, very impressive for an indie release. (The album’s sales exploded in the wake of the success of Nevermind.)

But by this time, Bleach drummer Chad Channing was history. Osborne knew Dave Grohl from sharing bills with Grohl’s band, Scream. After Scream’s bassist quit, Grohl called Osborne in desperation, and Osborne hooked him up with his old buddies in Nirvana. “Chris and Kurt liked Dave because he hits the drums harder than anybody,” says producer Butch Vig.

In August 1990, Nirvana recorded six tracks with Vig for a planned Sub Pop album. Bleach was very good, but Cobain had returned to the studio with songs that were a quantum leap past anything he’d done before.

Meanwhile, Sub Pop had begun talking to major labels about a distribution deal. Figuring that if they had to be on a major label, they might as well choose it themselves, the members of Nirvana began shopping the Vig demos. Only a major could afford to buy Nirvana out of their Sub Pop contract, and major distribution would get their punk to the people. “That’s pretty much my excuse for not feeling guilty about why I’m on a major label,” says Cobain. “I should feel really guilty about it; I should be living out the old punk-rock threat and denying everything commercial and sticking in my own little world and not really making an impact on anyone other than the people who are already aware of what I’m complaining about. It’s preaching to the converted.”

A bidding war broke out among a handful of labels. Nirvana signed to DGC, the label run by entertainment magnate David Geffen, a subsidiary of giant MCA and the home of Guns n’ Roses and Cher. The band received $287,000 in advance money.

The group approached R.E.M. producer Scott Litt and Southern pop maestro Don Dixon, but neither wound up taking the job, and the band chose Vig to produce instead. During rehearsals for the album, one song really stuck out. “As soon as they started playing ‘Teen Spirit,’ ” Vig says, “it was awesome sounding. I was pacing around the room, trying not to jump up and down in ecstasy.”

Nevermind was recorded last spring for $135,000, including living expenses, mastering and even Vig himself (he has since renegotiated his deal). Slayer producer Andy Wallace mixed the album. Vig knew something was up when all sorts of people started asking him for advance tapes; now he’s besieged with offers to produce bands and “make them sound like Nirvana.”

Just last September Novoselic and Cobain were so poor, they had to pawn their amps; now Cobain gets twenty bucks out of the cash machine and finds there’s another $100,000 in his account. When Novoselic told a friend he’d bought a five-bedroom house in Seattle, the friend pointed out that the payments would just be another headache. “What payments?” Novoselic replied. He’d paid for the house in full.

“A lot of people ask me: ‘When’s he going to buy you a new car? When’s he going to buy you a house?’ ” says Cobain’s mother. “I couldn’t even accept it if he offered it. We could have helped him along if we would have realized that this was really going to be something. We thought he’d get over it. I wish we would have helped him out a little more. He owes us nothing.”

Nirvana, however, owes DGC another record, which the band will likely start recording late this fall or early winter. Says Jonathan Poneman, “Either Kurt is going to create something that is an ornate masterpiece, or he is going to create something angry and filled with the rage and confusion.” Butch Vig thinks it might be a low-key acoustic album.

“I have a pretty good idea,” says Cobain. “I think both of the extremes will be in the next album – it’ll be more raw with some songs and more candy pop on some of the others. It won’t be as one-dimensional.”

One-dimensional or not, there’s a good chance Cobain’s audience just doesn’t get his message. The antimacho “Territorial Pissings” was used as background music for a football show; “Smells Like Teen Spirit” might suffer the same fate as “Rockin’ in the Free World” or “Born in the U.S.A.” – listeners may not get the irony at all. Actually, Cobain called it in the chorus to Nevermind‘s “In Bloom” – “He’s the one who likes all the pretty songs/And he likes to sing along . . . /But he knows not what it means.” Cleverly, the song is a natural-born sing-along, trapping listeners into the joke.

According to Nils Bernstein, most Nirvana fan letters are along the lines of “Hey, dude, I saw your video and bought your tape! You guys kick ass!”

“Everybody says, ‘You guys kick ass,’ ” says Bernstein. About half ask for the lyrics to “Teen Spirit” (the complete lyrics to Nevermind will be included with the next single, “Lithium”). Most letter writers are between ten and twenty-two, write on notebook paper, buy cassettes and watch MTV. “There’s not very many sexual letters,” says Bernstein, “which is a drag. The ones from prison are the best ones; also the ones from the military.” And what do soldiers say? “They say, ‘Hey, you guys kick some ass!’ ”

Cobain accepts that much of his new audience is made up of the same types who hassled him in high school. “I can’t have a lot of animosity toward them, because I understand that a lot of people’s personalities aren’t necessarily their choice – a lot of times, they’re pushed into the way they live,” he says. “Hopefully, they’ll like our music and listen to something else that’s in the same vein, that’s a bit different from Van Halen. Hopefully, they’ll be exposed to the underground by reading interviews with us. Knowing that we do come from a punk-rock world, maybe they’ll look into that and change their ways a bit.”

But it’s doubtful that most of them ever will. “Yeah, it seems hopeless,” Cobain says with a sigh. “But it’s fun to fight. It gives you something to do. It relieves boredom.” He laughs.

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario